Seeing a house as a toad and meeting many old folk hand in hand. This is the city as I saw it.

Read More

Jack Frost nips at your toes, then goes and takes a bath in the nearby river. It freezes. Time to dust off the ice skates!

Read More

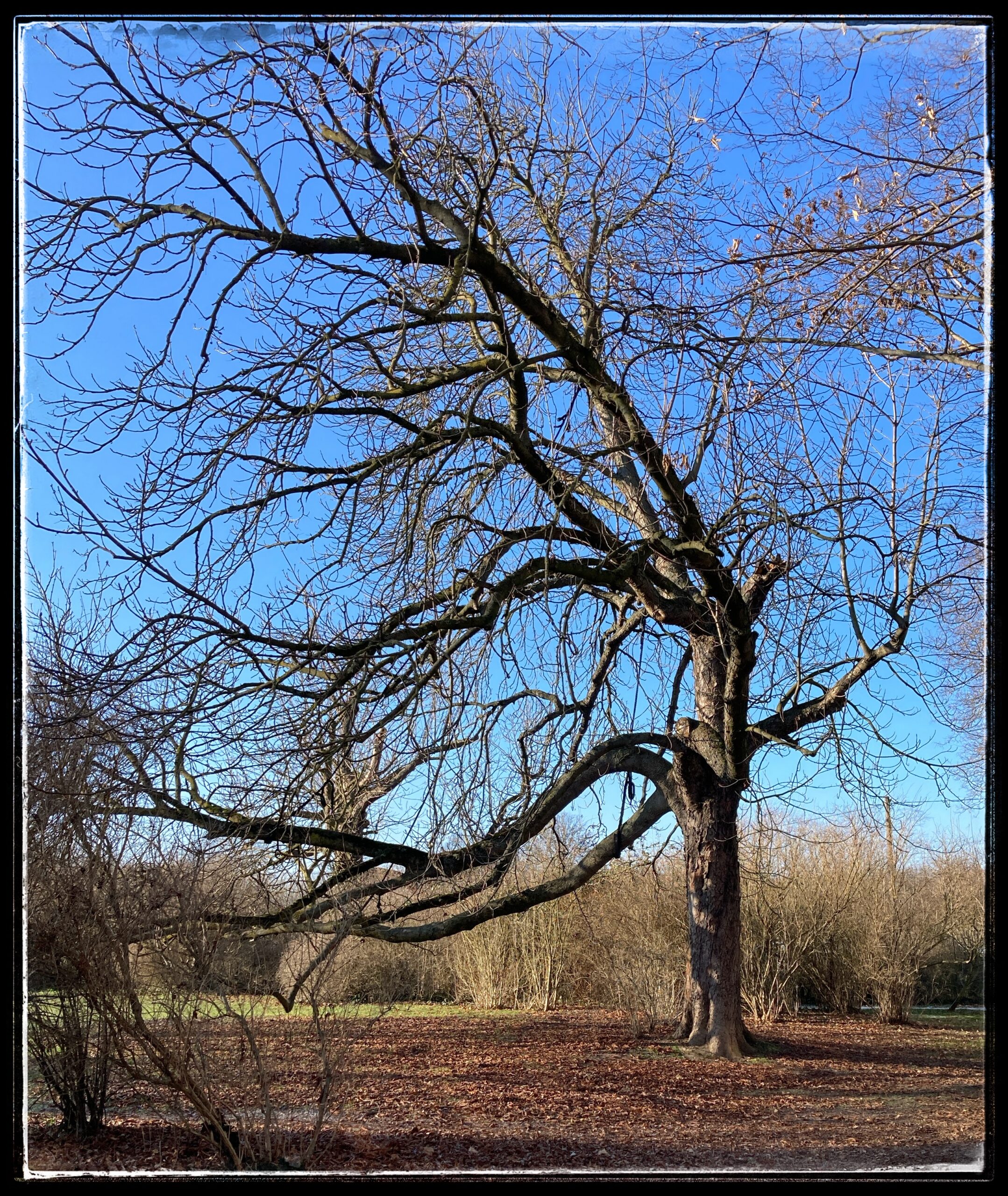

A bright winter's day in which are reaching trees, walking crows, and UFOs. There's also a ball of wool ...

Read More

It’s that time between Christmas and New Year, the special week I like to call Seven Days of Sod All. That’s right, even Moles take hols.

Read More

I decide to take the medieval Via Imperii to the drug store. It's out of my way, but it's ancient. And besides, the sun is shining ...

Read More

Some things creep up on you without you noticing: crows feet, dried apricots(*), JWs. Christmas should not be one of those things. It’s big, it’s shiny, it’s loud. It starts in October. Yet here it is.

Read More

A picture of a cartoon, egg-shaped bee with purple-magenta stripes on its yellow body. It has two black dots for eyes, a big, smiling mouth, and rosy pink cheeks. It's borne aloft on two tiny white wings. I’m out on the bi-weekly bean run. The weather may be grey, but…

Read More

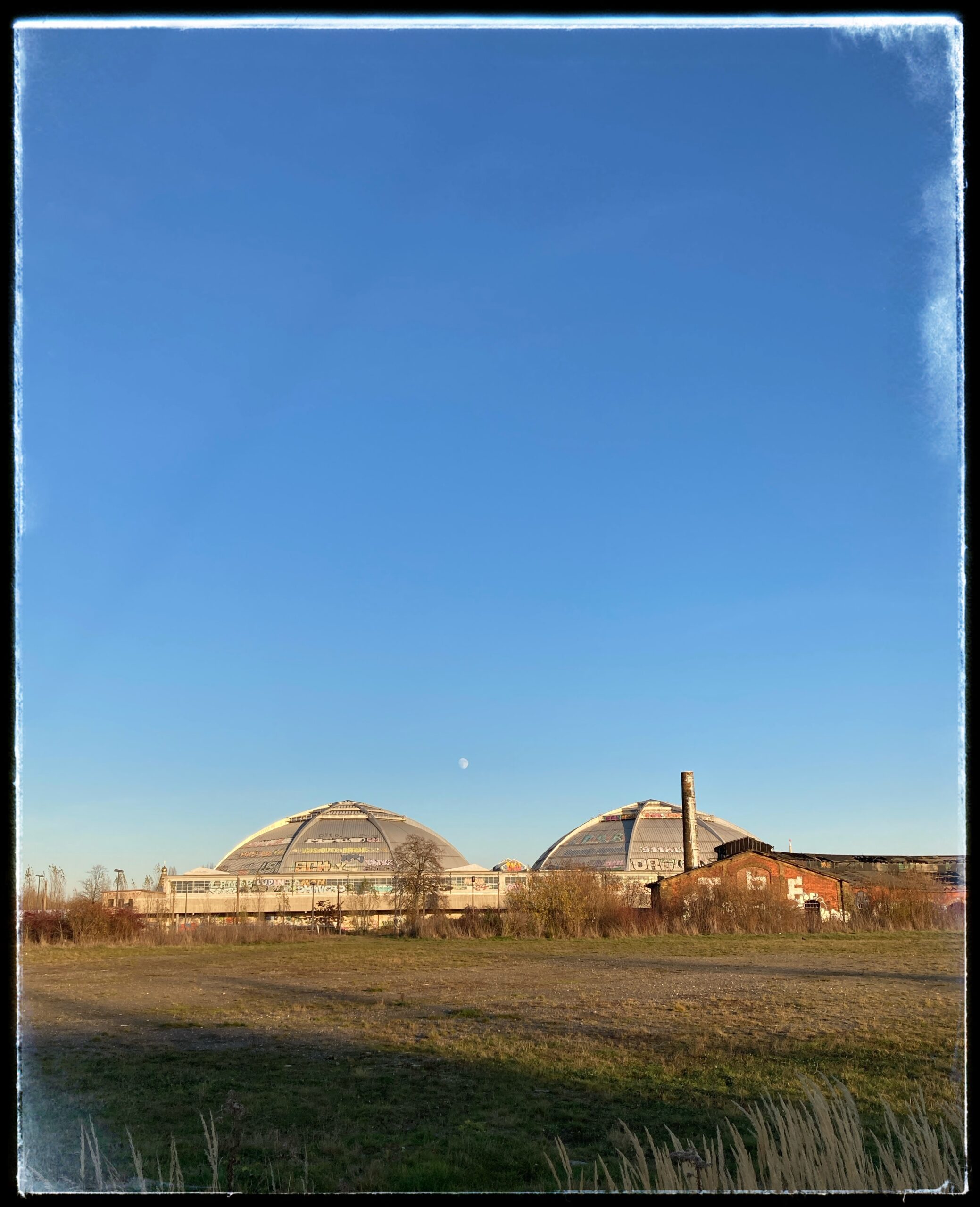

Near the MDR railway station in Leipzig is a giant concrete brassiere daubed in colourful graffiti. It’s called the Kohlrabi Circus, and it’s not what you think.

Read More