All the world’s a stage / And all the men and women merely players.

As You Like It (2.7)

There’s a music to the motion of things, if you listen. A soft harmony you can sit and hear, sometimes faint and far, sometimes near. You may have to sit for hours or days; sometimes a minute’s enough.

Or miss it. Who am I to tell you what’s tuneful?

First Movement

Our symphony begins with rays of sun in an overcast week. It’s getting on for supper but the bath of golden light’s just too enticing. We lace our shoes and leave the flat before we can change our minds, heading for the heights of Fockeberg.

Oh, the air’s sweet and the birdsong inviting. We bask atop the hill’s tonsure, turning this way and that, grinning like children.

“Shall we sit for a bit?” says The Mathematician.

“Sounds good. On the wall?”

She nods, and we take a seat next to a young man on his back, reading. We close our eyes and bathe.

“This is so nice,” The M sighs.

“It really is.”

A few moments of bliss go by, and then I hear a tiny voice.

“Are you sleeping?”

I open my eyes and squint. A two-year-old in a pointy blue cap is staring at me. He has a chunky brown treat in each hand. He takes a bite of one.

“Oh, that looks yummy,” I say.

He continues to stare, chewing. He swallows.

“Are you sleeping?”

He looks to his mum to make sure he’s saying it right.

“No,” I say. “Just enjoying the sun.”

He puts the rest of what’s left in his right hand in his mouth and looks at me somewhat doubtfully, cheeks bulging. Then he wanders over to the horizontal reader and tries to steal his bottle of Club Mate. His mum retrieves him, and as I close my eyes, I hear him being told that people do this when they enjoy the sun, because, you know, blindness.

We sit there for longer than planned. This, of course, generates much interest in my pointy-hatted friend. At various intervals I’m told that the sun is up, that it’s “over there,” that there’s a plane overhead, and that there’s a fire-coloured beetle crawling along the wall beneath my leg. I’m then, of course, obliged to lift my leg so that Pointy Hat can follow it on its journey.

It goes into a crack. He squats and watches.

“There’s moss in here,” I say, pointing to a few small clumps of fuzzy green. I stroke it. “It’s soft.”

“It’s spiky,” says Pointy Hat.

I frown.

“It spiky?” repeats The Mathematician.

Pointy Hat nods.

“No, moss is nice and soft. See? You try.”

He seems unsure.

“I think he’s talking about the bug,” says The M.

“Oh. Yes, the bug might be spiky.”

He seems satisfied with this and wonders off to steal some beer.

We talk to the parents of our new friend, a former ballet dancer turned stage manager and a current opera house employee. Lovely people. As the sun sets behind the trees, they decide to take their little man home. The Mathematician and I decide to head off too.

Second Movement

The next day sees us in the company of The Mathematician’s parents. We brunch, drink coffee, and talk as a light rain falls on our plans. But we’re not deterred and arrive only slightly damp at the Grassi Museum. A sour old woman serves us, the kind who, if carved as the figurehead of a ship, would make the waves reluctant to cross the bow. We venture into the large collection of historical musical instruments and see enough shaped wood to make a beaver blush.

Everything from the Renaissance to the Modern is on display, but the serpent and shawm catch my eye. What sinuous lines and intricate craftsmanship. I finger a nearby info panel to hear a sample of their sound and wonder what it must have been like to hear them played live, five centuries ago.

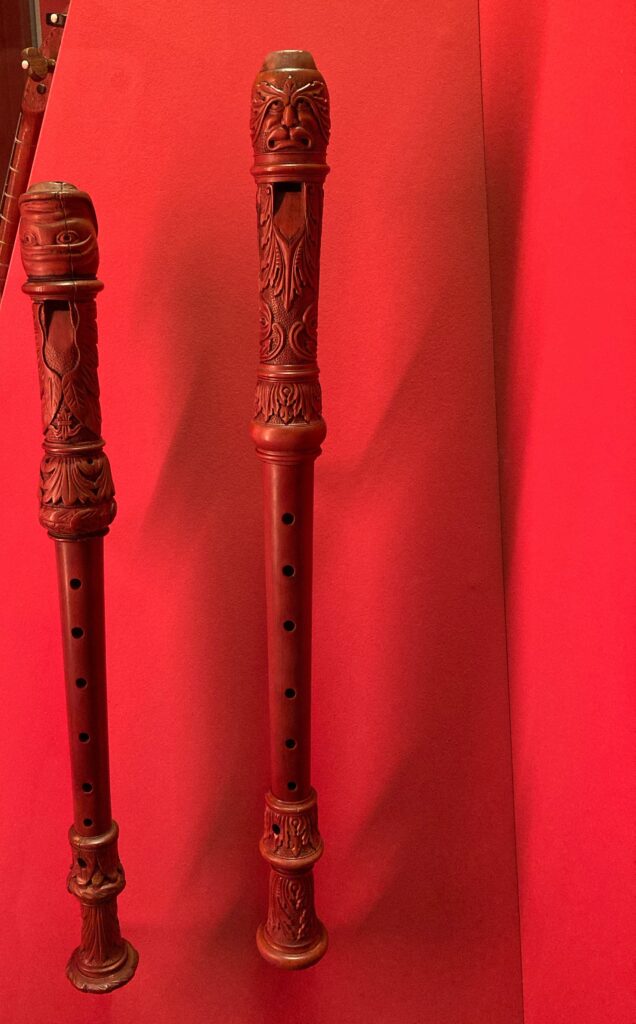

I find a few recorders with intricately carved head- and foot joints and monstrous mouthpieces, like tiny angry dryads full of holes. I want one. It could join my troupe of finely-tuned furniture.

I noodle a bit on a harpsichord, marvelling at how soft and warm the keys are, and how gentle the sound. Half a millennium of music in these halls, entire epochs of creativity and expression. I hear the sound of rain against the windows, the notes of a mile-high instrument.

Third Movement

We dine in ConnStanza and walk round the corner to UT Connewitz for an evening of Bach and Pisendel improvisations. Except it’s not. Four musicians and two dancers take the stage, and there’s not a single violin among them. Turns out the information on their website was a bit muddled: we’ll be getting improvisations, yes, but from the Renaissance period, not the late Baroque.

One of life’s lovely mistakes, because now, on stage, are two shawm players, along with a cornet and trombone. (A historical bagpipe will also make an appearance later.) I get to hear the very instruments I saw in the museum. The music is lively, the dancing courtly. We’re nobles in the Court of Margaret of Austria, we’re told. At one point, the players solicit five notes from us, then proceed to improvise around them. The dancers ask us to choose patterns of footwork to accompany this piece. I only half listen — I’m enchanted by the huddle of musicians who are shaping their new piece by softly singing.

When the concert is over, attendees of that day’s improvisation workshop are invited to come up on stage and play. We stay and listen as men and women of all ages and instruments harmonise, some with bold flourishes, others with modest ornament. The conductor regularly kneels on the stage to draw a stave and a few notes on a piece of paper. He places it on a low music stand, the musicians lean in and look, the soundscape changes.

It’s like watching a breeze move over a lake. I sit awhile on this shore, marvelling at the symphony of small connections.